Simone Cremaschi (Bocconi University, Milano, Italy) and Juan Masullo (Leiden University, Netherlands)

Published in Comparative Political Studies, May 2024. Go to the paper on the publisher's site.

Abstract

Can past wartime experiences affect political behavior beyond those who lived through them? We argue that local experiences of armed resistance leave political legacies that “memory entrepreneurs” can translate into contemporary political action via a community-based process of intergenerational transmission consisting of three core activities – memorialization, localization, and mobilization. We empirically substantiate this argument in Italy, where an intense armed resistance movement against Nazi-Fascist forces took place in the 1940s. We combine statistical analysis of original data across Italian municipalities and within-case analysis of a purposively selected locality to show how the past impacts the present via the preservation and activation of collective memories. This study improves our understanding of the processes of long-term transmission, emphasizes armed resistance as a critical source of the long-term political legacies of war, and explores its political effects beyond electoral and party politics.

Introduction

Many European countries have experienced intense episodes of armed resistance to foreign occupation and authoritarian rule, especially during World War II. Examples include the partigiani in Italy, the maquisards in Vichy France, the andartes in Greece, and the partizani in the former Yugoslavia. These experiences were essential for post-war national regeneration and political reconstruction and constituted a foundational moment for establishing democratic systems throughout the continent. However, in contradiction to the principles, identities, and institutions upheld by these resistance movements, far-right parties with explicit fascist and neo-Nazi ideologies have recently emerged or gained significant strength in some of these countries. The success of these parties, and mainstream political forces’ inability to muster a consensus to curb them, challenges the notion that critical past events leave long-lasting legacies that can shape current political dynamics.

Against this backdrop, we argue that past experiences of wartime resistance can shape contemporary politics in meaningful ways. The formation, preservation, and constant reinforcement of collective memories extend the reach of the political ideals defended by those who resisted beyond individuals who lived through the war, and can be translated into various forms of political action. To explain how past wartime experiences are linked to contemporary political attitudes and behavior, we detail a community-based transmission process based on three core activities (memorialization, localization, and mobilization) carried out by national and local actors invested in preserving memory – who we call “memory entrepreneurs.”

We empirically evaluate this argument in Italy, which experienced an intense period of partisan resistance against Nazi-Fascist forces during its civil war (1943–45). First, we leverage spatial variation in the presence of partisan bands and a novel behavioral measure of anti-fascist preferences from a recent nationwide, grassroots campaign to establish a statistical association between an area’s experiences of resistance during the war and contemporary anti-fascist preferences. This association is robust to multiple model specifications, alternative outcome measures, and key alternative explanations.1 In a second step, we offer qualitative within-case evidence of the theorized process linking past experiences of resistance to contemporary support for the anti-fascist campaign.2 We illustrate how physical and experiential memorialization, anchored in local referents and led by a committed group of memory entrepreneurs, helps explain how collective memories of resistance have been formed and kept alive, transmitted across generations, and tapped into to mobilize support for the campaign.

This study makes three core contributions to the growing literature on the long-term legacies of war. First, we heed recent calls to go beyond estimating effects to explore the mechanisms through which historical legacies are transmitted (e.g., Balcells & Solomon, 2020; Charnysh & Peisakhin, 2022, p. 434; Davenport et al., 2019; Simpser et al., 2018; Walden & Zhukov, 2020, p. 177). We theorize a community-based intergenerational transmission process and rely on process tracing to provide mechanistic evidence (Beach & Pedersen, 2019, Chap. 5) of how it operates within a single case. In doing so, we advance the debate on transmission mechanisms. We highlight that the political effects of wartime events are influenced by social actors’ efforts to steer and preserve collective memories, stressing that the meaning of historical events should not be taken as given (Basta, 2018) and that social context plays a crucial role in the persistence of political attitudes (Tavits, 2013; Villamil, 2020, 2022; Wittenberg, 2006). Furthermore, we show that intergenerational transmission can also be community-based, complementing or even substituting, the role of family ties, formal institutions, and state sanctioning.

Second, we show that wartime experiences other than violent victimization, like armed resistance, can have long-lasting political effects as they can serve as powerful references for creating and preserving collective memories.3 In doing so, we push scholarship on the historical legacy of war beyond the “violent bias” that is common in conflict studies (Arjona & Castilla, 2022). Finally, by focusing on contemporary grassroots political processes and less institutionalized politics, we join recent studies (e.g., Arias & De la Calle, 2021; Charnysh & Riaz, 2023; Costalli et al., 2024; Lazarev, 2019; Osorio et al., 2021; Wayne et al., 2023) in shifting attention away from the dominant focus on the persistent effects of wartime experiences on electoral and party politics.

Our study provides new evidence that past wartime events shape contemporary political behaviors and offers novel insights into how local communities can preserve and transmit collective memories to keep legacies alive and activate these memories to alter political outcomes. As such, our work provides further evidence that symbolic politics can have real, non-symbolic political consequences (Balcells et al., 2021; Rozenas & Vlasenko, 2022; Villamil & Balcells, 2021).

Wartime Political Legacies

Previous research has established that exposure to violence affects the social and political attitudes of combatants and war survivors (Bauer et al., 2016; Blattman, 2009; Gilligan et al., 2014; Voors et al., 2012). More recent studies have further shown that wartime violence can have long-term political effects, which influence both the demand and supply sides of the electoral market beyond those who directly experienced violence (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2015a, 2018; Fontana et al., 2023; Fouka & Voth, 2023; Rozenas et al., 2017; Villamil, 2020). For example, Western Ukrainian communities exposed to Soviet violence during the 1940s were found to be less inclined to vote for pro-Russian parties six decades later (Rozenas et al., 2017), and residents of Greek prefectures that suffered massacres by occupying German forces during World War II more strongly supported anti-German parties during the 2009 debt crisis (Fouka & Voth, 2023). In general, there is growing evidence that wartime victimization can lead to the rejection of political identities, ideas, and institutions associated with the perpetrator (Balcells, 2012; Fontana et al., 2023; Fouka & Voth, 2023; Lupu & Peisakhin, 2017; Rozenas et al., 2017).

Work in this field has greatly advanced our understanding of the long-term effects of war. However, its focus has been too narrow in two important respects. First, reflecting a more general bias toward violence in war studies (Arjona & Castilla, 2022), much of this research has focused on the persistent effects of past victimization (e.g., Balcells, 2012; Fouka & Voth, 2023; Meriläinen & Mitrunen, 2023; Rozenas et al., 2017; Rozenas & Zhukov, 2019; Villamil, 2020; Zhukov & Talibova, 2018). With few exceptions,4 whether (and how) other wartime dynamics can have long-lasting political effects has been largely overlooked. Second, few scholars have explored long-term legacies beyond the ballot box and party politics.5 Therefore, we know less about how wartime experiences shape grassroots and less institutionalized politics in the long run. We help broaden the focus of this body of work by examining the long-term effects of armed resistance on a grassroots political campaign.

Research on the long-term effects of war experiences – and on historical legacies more generally – has begun to account for factors that mediate long-term effects. Recent studies have identified conditions under which the past can affect the present, including the degree to which present events resemble the past (Fouka & Voth, 2023), the presence of clandestine networks (Villamil, 2020), the absence of credible threats of retribution (Rozenas & Zhukov, 2019), local communities’ capacity to bypass revisionist efforts (Villamil, 2022), regime’s efforts to co-opt social mobilization (Albertus & Schouela, 2024) and the degree to which collective memory is institutionalized (Fouka & Voth, 2023). Furthermore, legacies have been found to be transmitted through family socialization (Lupu & Peisakhin, 2017; Nunn & Wantchekon, 2011; Voigtländer & Voth, 2012), community composition (Charnysh & Peisakhin, 2022), peer and neighbor effects (Cho et al., 2006), and educational and religious institutions (Wittenberg, 2006).

Despite these advances, the question of how legacies survive over long periods of time and across generations remains a central theoretical and empirical puzzle in both the general literature on historical legacies and the strand focusing on the long-term effects of war. There is no consensus regarding what transmits, maintains, and aggregates historical legacies (Balcells & Solomon, 2020; Davenport et al., 2019; Simpser et al., 2018; Walden & Zhukov, 2020; Walden and Zhukov 2020, 2020). This is partly because, despite remarkable progress in identifying and estimating how the past affects the present, these studies rarely trace the processes that link past experiences to contemporary outcomes within specific cases. Enhancing our understanding of how legacies are transmitted requires new research strategies to complement those typically used in the quantitative literature on the long-term legacies of war. We advance current debates on legacy transmission by carefully theorizing a community-based intergenerational transmission process and using process tracing to provide detailed within-case qualitative evidence of how transmission operates.6

Wartime Legacies & the Process of Intergenerational Transmission

We argue that the construction and promotion of collective memories are critical for keeping the legacies of wartime events alive.7 People neither automatically remember events nor objectively interpret them (Basta, 2018). Collective memories structure a community’s understanding of the past, forge collective identities, and, in turn, inform behavior (Antze & Lambek, 1996; Esposito et al., 2023; Eyerman 2001, 2004; Fouka & Voth, 2023; Shamir & Arian, 1999; Wayne & Zhukov, 2022; Wayne et al., 2023). Therefore, a collective memory of wartime events must be created before legacies can be passed down. This is especially the case when the events in question do not leave a clear mark through trauma, which, unlike victimization or repression, is often the case for armed resistance.8

We argue that localities that historically resisted external threats during war are particularly favorable environments for the formation, preservation, and promotion of collective memories. Although narratives of resistance might be promoted nationally, collective memory is more easily forged and preserved in these community settings. Actors invested in memory making can tap into physically and socially proximate referents to memorialize resistance. When these references are leveraged, residents are more likely to identify with narratives of resistance, and memorialization efforts are more likely to resonate with them. Consequently, people living in areas that were actively involved in resistance are more likely to have and defend political preferences that align with those of the resistance movement and to reject the identities, ideologies, and institutions the resisters fought against. Yet, for these collective memories to shape contemporary political outcomes, they must survive generational changes, reach beyond those who directly or indirectly experienced war, and be activated and translated into political action.

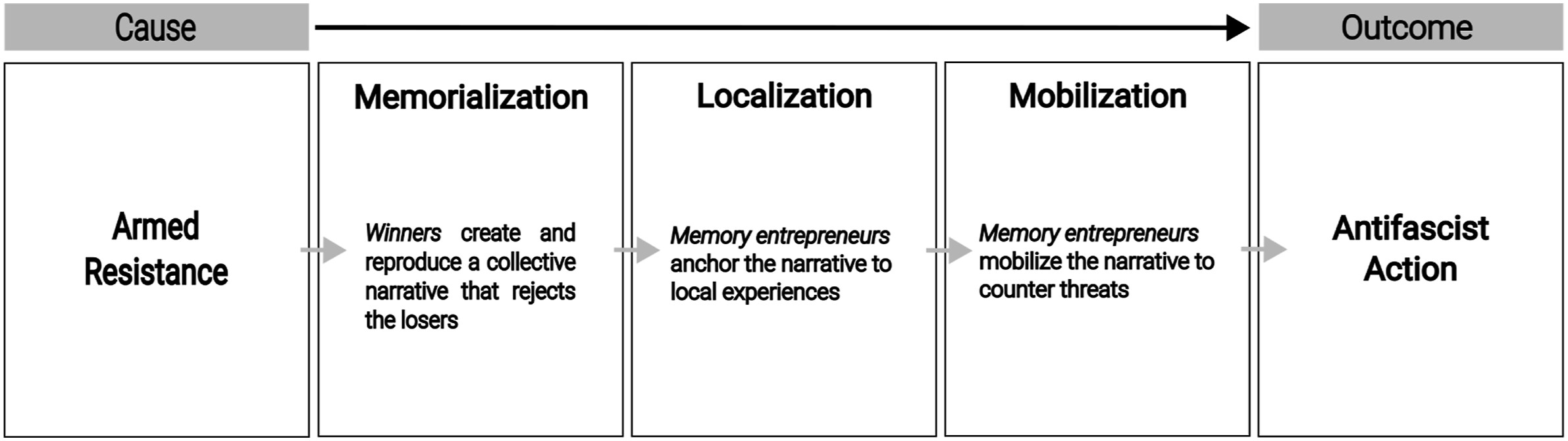

We propose that one way this is achieved is through a community-based transmission process that involves three key steps: memorialization, localization, and mobilization (Figure 1).9 This process facilitates the formation, preservation, and transmission of collective memories and puts them at the service of political action when needed. We do not contend that this is the only possible path connecting historical events with contemporary political action. We propose these three steps as jointly sufficient for the outcome but not necessary.

First, memories of a historically defining experience or event are created and preserved via memorialization (Jelin, 2007). To forge collective memories, actors we call “memory entrepreneurs” recall historical events to promote a particular interpretation of the past, amplifying some actions and events and downplaying others, and legitimizing some actors while disavowing and condemning others. As such, memorialization draws attention to specific wartime experiences to reorient thinking about past events and the actors involved.

The most common manifestation of memorialization is physical: monuments, statues, engraved plaques, and street and square names can shape how people value, identify with, and debate the past (Crampton, 2001; Johnson, 1995; Rozenas & Vlasenko, 2022; Turkoglu et al., 2023; Villamil & Balcells, 2021). These “sites of memory” (Nora, 1989, p. 7) are particularly effective at preserving collective memories because they make memory a visible and permanent part of public life for all members of a community regardless of their personal or family ties to the memorialized event. Memorialization also has experiential manifestations such as ceremonies, commemorations, demonstrations, rituals, and festivals. These symbolic practices complement physical memorialization as they actively involve community members in forming and preserving collective memories and can target specific segments of the population. Together, physical and experiential memorialization project collective memories onto a shared social and political landscape and institutionalize them. Collective memories crystalized in permanent symbols and reinforced through interactive practices help extend the meaning of past events to those who did not live through them (Balcells et al., 2021; Hamber et al., 2010). Memorialization is therefore a vital vehicle for intergenerational transmission.

Different forms of memorialization have been found to effectively shape political attitudes and behaviors in various contexts. For example, the Stolpersteine (“stumbling stones”) project – the world’s largest decentralized Holocaust memorial – commemorating the victims and survivors of Nazi persecution across various European cities has been found to shape the electoral behavior of those exposed to it in Berlin (Turkoglu et al., 2023). Experiential memorialization in the form of transitional justice museums in places as diverse as Chile, Romania, and Northern Ireland has also been found to shape political attitudes (Balcells & Voytas, 2023a, 2023b; Balcells et al., 2021; Light et al., 2021).10 Similarly, there is evidence of the effects of commemoration days. Participating in Holocaust Day in Israel and in Remembrance Day, Liberation Day, and Queen’s Day in the Netherlands has been found to increase national identification and pride (Ariely, 2019; Meuleman & Lubbers, 2013).11

Second, localization makes memorialization efforts more effective. It involves using local referents – such as battles won, brave leaders, or defining events or spaces – to anchor memorialization locally.12 Narratives of past foundational events are commonly generic and formed and promoted at the national level (in the case of war, usually by the winning side). Local memory entrepreneurs can take advantage of the social and physical proximity of the memorialized experience to make these generic narratives more relatable and accessible to communities.13 Thus, by increasing resonance and self-identification, localization reinforces memorialization.

Localization lies at the core of numerous successful memorialization efforts. The Stolpersteine initiative, where a ten-cm brass plate located in front of victims’ last place of residence, emphasizes that they did not live “anywhere” but “right here” (Turkoglu et al., 2023), and the Greek government’s granting certain towns that endured reprisals during the German occupation “martyr status” (Fouka & Voth, 2023), are expressions of localization. Memorialization has a significantly more profound impact when it hits close to home. Discovering that a person who once resided in one’s building or street was deported, as symbolized by a “stumbling block,” is likely to resonate more deeply than the awareness that many individuals were deported from the country, as represented by a generic monument commemorating Nazi regime victims. Likewise, living in an area officially designated as having borne a disproportionate burden of atrocities heightens awareness and condemnation of these atrocities.

The final step in the process is mobilization. Even when collective memories forge collective identities and shape political preferences, they do not automatically translate into political action. Those invested in local memory making help translate political identities into concrete political action when it is most needed. Mobilization consists of alerting people to threats to the values, identities, and institutions upheld by the collective narratives, and facilitating political action (such as demonstrating and voting) to counter the work of “revisionist” agents. Although collective memories can be mobilized anytime, mobilization is likely to be more effective when collective narratives are threatened and the present threats most closely resemble past experiences. The more people associate current threats with the values, norms, and ideals evoked by collective memories, the more prominent the past will be in their minds and the more likely they are to be mobilized into political action. Association increases the salience of the past, making it more likely to influence present attitudes and behavior (Fouka & Voth, 2023; Rozenas & Vlasenko, 2022). Mobilization has been found to be crucial in various instances where historical political conflicts have shaped contemporary political behavior. For example, mobilization by Catholic lay organizations played a definitive role in linking 19th century oppression of German Catholics with diminished support for far-right parties today (Haffert, 2022).

As noted above, memory entrepreneurs – actors deeply invested in preserving, transmitting, and activating collective memories – are the crucial entities behind this process of intergenerational transmission. While these actors can be individuals, collective memory entrepreneurs, in the form of civic associations for example, tend to play a more decisive role in the process (Haffert, 2022; Villamil, 2020; Wittenberg, 2006). This is because collective actors are more likely to engage in long-term efforts, cut across local divisions, and have more influence within communities. While they are not necessarily professional politicians operating in the electoral arena, their role resembles that of “political entrepreneurs” in electoral and party politics (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2015a; De Vries & Hobolt, 2020; Tavits, 2013). Not only do they mobilize people into political action at specific times; they also work continuously to increase the salience of specific issues and ensure that contemporary politics are interpreted through the lens of collective memories.

The Case of Italy

Partisan Resistance during the Italian Civil War and Its Post-war Legacies

Italy withdrew from World War II in September 1943 after signing the Cassibile Armistice with the Allied forces. Germany then invaded from the North to prevent the Allies’ advance from the South.14 Germany rapidly defeated the Italian forces, freed Mussolini, occupied northern and central Italy, and established the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI), the last incarnation of the Italian fascist state. The German occupation and establishment of the RSI triggered fierce resistance among various sectors of the Italian population, leading to a civil war that lasted from September 1943 to May 1945, inflicted around 117,000 battle-related deaths (Istituto Centrale di Statistica, 1957) and killed approximately 10,000 civilians (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2015a, p. 23; Dondi, 1999).15

In occupied Italy, armed resistance was organized to fight both the German forces and fascist militias. After some initial insurrections, the National Liberation Committee (Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale, CLN) organized (most) partisan resistance bands throughout northern and central Italy.16 While the resistance movement was initially fragmented and resource-poor, it grew significantly during the war to 100,000–300,000 fighters (Bocca, 1995, pp. 493–494; Corni, 2000, p. 178; Pavone, 1994; Rochat, 1975). A large number of partisans fought in communist and socialist brigades (Pavone, 1994), but the movement also had important Catholic, liberal, and autonomous components (Bocca, 1995; De Rosa, 1998; Pavone, 1994, pp. 20–38, 416–433 Valiani et al., 1971; Vecchio, 2022, Chap 5–8).17 Although partisan bands were also present and active in cities and flatlands, the largest contingents operated in the mountainous districts of the Alps and Apennines. Between mid-1944 and April 1945, the movement stably occupied all alpine valleys and hilly areas of central and northern Italy (Bocca, 1995, p. 5).

Numerous partisan formations originated in the ranks of both long-standing political dissidents who remained in hiding during the fascist regime and soldiers from disbanded units of the Royal Italian Army. Many of these early instigators returned home seeking to galvanize the local population, resulting in recruitment and operations that were largely community based. While these partisan groups were mobile, their activities were typically confined to a particular municipality or province. Although the CLN had its central headquarters in Rome (and later another one in Milan), it orchestrated and coordinated the actions of these bands through regional and local chapters. This close connection to the local terrain and its inhabitants helped it garner widespread popular support (Bocca, 1995; Pavone, 1994; Peli, 2017).

The war officially ended on April 28, 1945, 3 days after the CLN proclaimed a general insurrection in northern Italy. On June 2, 1946, elections and a popular referendum were held to select the assembly charged with writing the new constitution and to decide whether the new state would be a monarchy or republic. This process eventually led to the establishment of the new democratic republic, enshrined in political myth as “the ‘child’ of the resistance” (Corni, 2000, p. 180). Virtually all the main political parties represented in the first democratically elected parliament had participated in the resistance movement.

The importance of partisan resistance in Italy, as in other European countries, rests as much on its practical contribution to liberation as its role in national reconstruction (Cooke, 2013; Lagrou, 1999). Partisan veterans, with state backing, transformed the experience of wartime resistance into a collective narrative to transmit to future generations. This narrative involved praising partisans’ contribution to the country’s liberation and rejecting the identity, ideas, norms, and institutions of fascism. As such, it offered a redemptive device to reestablish a positive image of the Italian people after almost 20 years of widespread acquiescence to the fascist regime (Gentile, 2011, Chap 17) and to consolidate the democratic ideals espoused and fiercely defended by the Resistance. The narrative materialized in annual marches, plaques, monuments, and the naming of streets and squares whose importance can still be felt throughout the country (Cooke, 2013; Foot, 2009).

This process was not linear or uncontested, however. In the immediate aftermath of the war, deep-seated political divisions among the factions involved in the resistance movement – each crafting narratives that often framed their opponents as puppets of either the United States or the Soviet Union (Gentile, 2011, Ch.18) – relegated the commemoration of partisan resistance to the margins of the national public discourse (Santomassimo, 2003). Partisan resistance did not fully become a foundational narrative for the construction of national identity until the 1960s, when the Communist Party and the Christian Democracy gradually reconciled (Cooke, 2013; Gentile, 2011; Santomassimo, 2003). On the 20th anniversary of the Liberation in 1965, the Minister of Public Education initiated a series of programs to promote the memory of the Resistance in schools (Santomassimo, 2003). Memorials commemorating the Resistance were constructed throughout the country; most were built between 1969 and 1975 (Cooke, 2013, p. 114). Medals of military gallantry were awarded to towns that contributed significantly to the Resistance until the early 2000s, and institutes were created throughout the country to study the history of resistance. April 25, marking the day of the final insurrection, was established as Liberation Day, and June 2 as Republic Day to commemorate the 1946 referendum. These memorialization efforts institutionalized the collective memory of the Italian resistance.

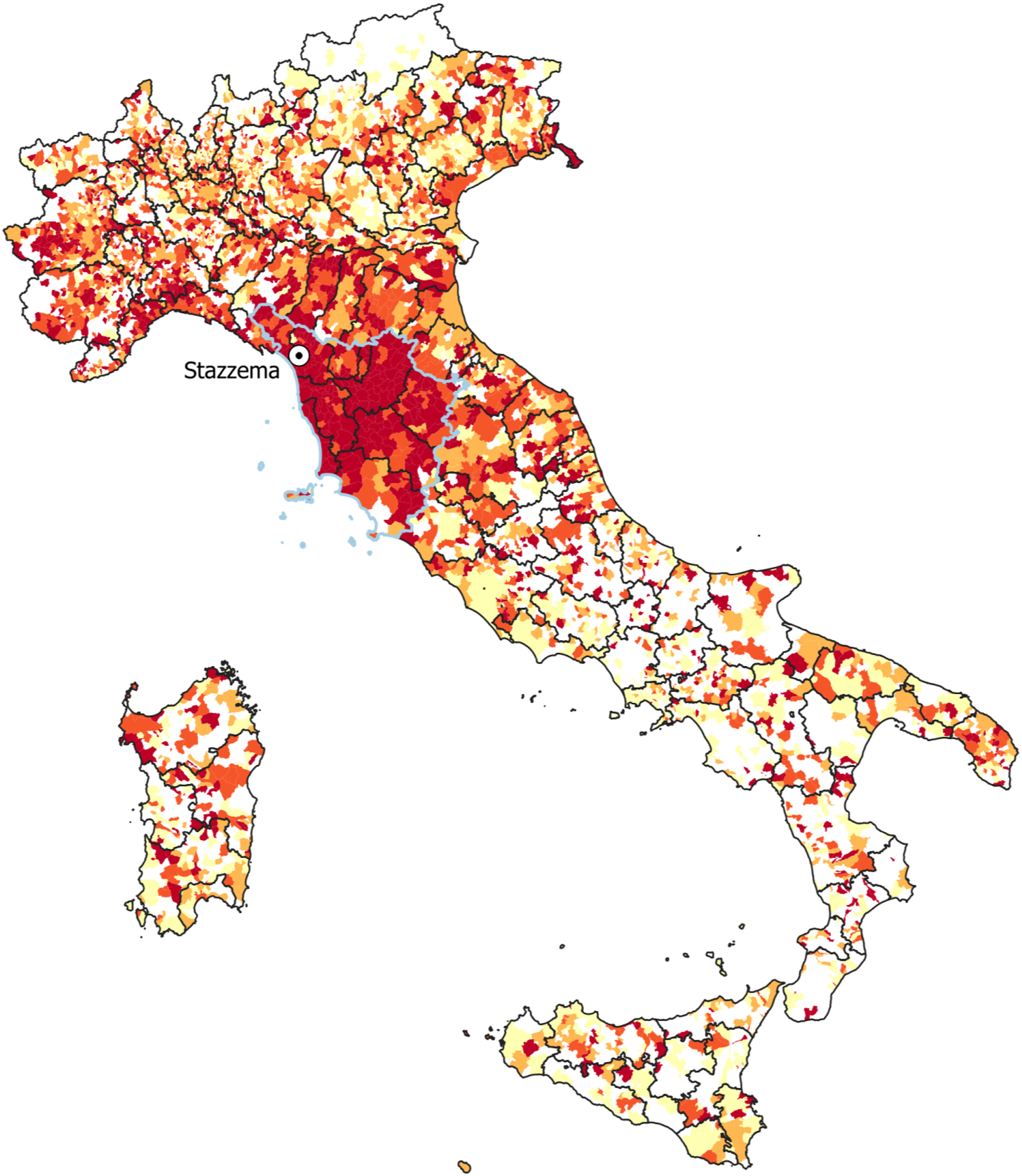

The Anti-fascist Law Campaign, 2020–21

In 2020, in response to increasing support for far-right parties and movements, including openly neo-Nazi or neo-fascist organizations, the mayor of Sant’Anna di Stazzema, a town in the Toscana region, launched a bottom-up popular legislative initiative (legge di iniziativa popolare) to ban neo-Nazi and neo-fascist propaganda known as the Anti-fascist Law.18 For this type of initiative to be discussed in Parliament, 50,000 signatures from registered voters had to be collected in person.19 Between October 19, 2020 and March 31, 2021, registered voters from the entire country could sign in support of the initiative at their local town hall or, in some cases, at stands organized by campaign promoters. Although some local chapters of the National Association of Italian Partisans (Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia, ANPI) helped collect signatures, the association was not officially involved in the campaign.20 Yet the campaign still managed to collect 240,000 signatures nationwide (Figure 2 maps their distribution). We exploit this fine-grained, contemporary measure of anti-fascist mobilization to study the local legacies of the resistance movement.

Figure 2. Signatures for the Anti-fascist Law, March 2021.

Notes: Darker colors indicate a higher proportion of signatures within a municipal’s population. Black lines indicate 2021 provincial borders. The light blue line highlights Toscana’s regional borders.

Research Design

Our integrative multi-method research design (Goertz, 2017; Seawright, 2016) combines statistical analysis of geo-localized cross-municipal data and in-depth within-case analysis based on original qualitative data collected during fieldwork. The statistical analysis first establishes a robust association between the local presence of partisan bands in the 1940s and current anti-fascist preferences at the municipal level and casts doubt on important alternative explanations. The case study traces the process underlying this association, offering within-case evidence of the presence and operation of the theorized process of intergenerational transmission.

The results of our quantitative analysis support the argument that past experiences of armed resistance influence contemporary local political preferences and behaviors. These results are robust to a number of checks including different model specifications, matching procedures, and alternative outcome measures, as detailed below. Yet our quantitative design has limitations in terms of causal inference. Our qualitative analysis further strengthens the plausibility that this relationship is causal by offering within-case evidence of the operation of our theorized process linking armed resistance to anti-fascist preferences. Carefully tracing the process in a carefully selected case allows us to make case-level inferences by assessing the degree of match between predicted evidence and empirical observations from the case (Beach & Pedersen, 2019).

Quantitative Component

Our statistical analysis examines how local historical experiences of partisan resistance explain spatial variation in contemporary anti-fascist preferences (measured as the number of signatures per municipality in the 2020–21 Anti-fascist Law campaign). The count of signatures, which we obtained from the campaign promoters, gives us a unique opportunity to assess the strength of anti-fascist preferences across Italian municipalities using a behavioral measure other than electoral politics, which originated in a grassroots campaign. In addition, as reported in Appendix A7, we explore the association with electoral politics, looking at party vote shares in the 2022 national elections.

Our main explanatory variable measures the presence of operational bases of armed resistance units.21 We digitalized maps showing the location of the armed bands during the war and created a dataset indicating which Italian municipalities hosted partisan bands between September 8, 1943 and April 25, 1945 (see Figure 3).22 A team of Italian historians gathered this data and created the maps, which were published in the Historical Atlas of the Italian Resistance (Baldissara, 2000). They crosschecked the information by triangulating multiple sources, including the archives of the Allied armed forces, Italian military, and partisan associations. This data constitutes the most complete historical source on the geographic distribution of partisan resistance in the country to date.

Figure 3. Distribution of partisan bands, 1943–45.

Note: Municipalities in red hosted at least one partisan band during the civil war. Black lines indicate 2021 provincial borders.

Given that our data for the dependent variable has a marked right-skewed distribution and large dispersion, we estimate variants of a negative binomial model (Cameron & Trivedi, 2013), with the following conditional expectation for the signature count23

where m denotes the municipality and p the province. The term Signaturesm,p represents the number of signatures collected in the municipality. The binary variable Resistancem captures the presence of at least one partisan band. is a vector of municipal-level controls, and α a constant and μp province fixed effects.24

Since our hypothesized community-based transmission process is less likely to unfold in large urban areas, we exclude municipalities with a population over 25,000 (roughly 5% of the total). We also exclude the five regions where formal resistance bands did not emerge since the Allies liberated these areas early in the civil war or even before its onset: the southern regions of Calabria, Campania, Molise, Puglia, Sicilia, and the island of Sardegna.25 The results remain robust when we do not apply these restrictions (see Appendix Table A7).

Our baseline model includes in the vector a number of control variables measured close to the date of signature collection. These contemporary controls allow us to adjust our estimates for several competing explanations. However, using contemporary controls could introduce bias into our estimates if the presence of partisan bands during the civil war also affected our control variables (Montgomery et al., 2018; Rosenbaum, 1984). We therefore try to select only contemporary controls that are unlikely to be influenced by the presence of armed resistance, such as demographic characteristics or access to broadband Internet. To address the possibility that the association between local partisan resistance and anti-fascist preferences could mask preexisting ideological differences between municipalities, we substitute controls in the vector with a set of variables accounting for the municipality’s pre-civil war characteristics using data from Acemoglu et al. (2022).26 Since municipal boundaries have changed significantly over the last century, we recalculate pre-war variables to reflect Italy’s current municipality structure (see Appendix A2). We discuss both sets of control variables in more detail in Section 6 (for descriptive statistics, see Appendix Tables A3 and A4). As an additional robustness check, we use three different matching techniques (inverse probability weighting, nearest-neighbor matching, and entropy balancing) to obtain a more comparable set of municipalities with and without resistance bands. Finally, following the procedures employed in other studies exploring long-term legacies (see Acharya et al., 2018, pp. 72–74), in Appendix A6 we examine the results of two national referendums held around the same time as the Anti-fascist Law campaign (in 2020 and 2022). This allows us to explore whether municipalities in which partisan bands were active exhibit different preferences than those in which they were not on policy issues related to the memory of the Resistance (but not on unrelated issues).

We also explore four main alternative explanations. The first is the possibility the possibility that the observed relationship between past resistance and current support for the Anti-fascist Law may be driven by left-wing preferences from before the war. To so do, we include the 1919 vote shares for the communists and socialists in our models with pre-war controls, and disaggregate the effect of partisan presence according to the ideological affiliation of the band (socialist and communist vs. other bands). Second, we examine whether the effect is driven by Nazi-Fascist violence rather than by experiences of resistance by including two measures of violence between 1943 and 1945: total episodes of violence and the number of victims by type (partisan vs. civilian casualties).27 Third, we investigate the possibility suggested by the campaign organizers that a large number of signatures resulted from personal and direct contacts between the campaign organizers and local actors. To do so, we run models that exclude the Toscana region (where the campaign started) and control for the distance to Stazzema (the municipality that initiated the campaign). Lastly, since COVID-19 restrictions could have affected the number of signatures, we run additional models controlling for COVID-19 intensity at the provincial level.

Qualitative Component

We use qualitative methods at two different stages of the study. First, before performing the statistical analysis, in December 2021 we conducted fieldwork in Stazzema in the Toscana region, where the anti-fascist campaign originated. Our goal was to validate our outcome measure by better understanding the process behind the campaign, how the proposal was promoted, and the key actors behind it. We interviewed the mayor of Stazzema and other key local actors involved in launching the initiative.

The second stage, which took place after the statistical analysis, sought to trace the empirical fingerprints of the proposed community-based transmission process in a carefully selected case to determine whether its constitutive parts were present and operated as we hypothesized. In April 2022, we conducted a detailed examination of a small, semi-rural, hilly town in the Emilia-Romagna region. We used three main data collection methods: direct observation, semi-structured interviews with key informants, and examination of local and community-kept archives, including textual and audiovisual documents.28This research has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bocconi University, reference number FA00583.

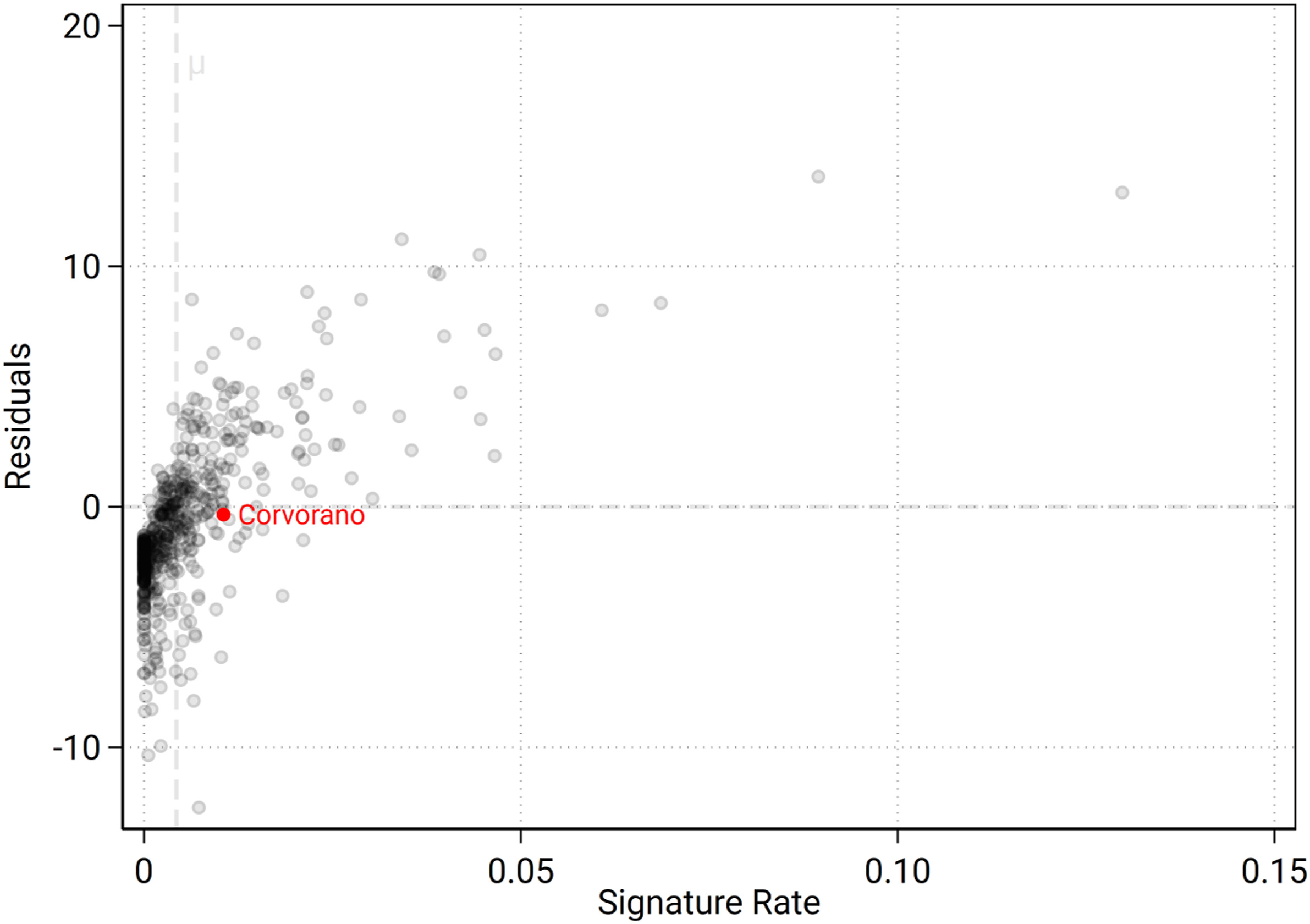

As our objective was to trace a process, we selected a case for which we had good reasons to believe the theorized process was present, combining guidelines from two different research traditions: process tracing (Beach & Pedersen, 2018; Goertz, 2017, Chap. 3) and nested analysis (Lieberman, 2005; Seawright & Gerring, 2008).29 First, following guidelines for the appropriate selection of cases for tracing causal mechanisms, we searched for a municipality that met two conditions: (1) resistance bands were active there in 1943–45 and (2) a large number of signatures for the Anti-fascist Law were collected. From the pool of municipalities that met these criteria, we looked for a case that met some basic requisite contextual conditions for the hypothesized process to unfold based on pre-fieldwork information. We sought a municipality (1) that was on the “national memory map” – for example, the Italian government had recognized its role in the Resistance and (2) with a presence of the “usual suspects” engaged in memory work – for example, local chapters of ANPI and the Italian Ricreative and Cultural Association (Association Ricreativa Culturale Italiana, ARCI).30 We excluded municipalities with characteristics that could inhibit our proposed process. For example, during our first round of fieldwork in Stazzema, campaign organizers indicated that they had relied on personal networks to collect signatures and had directly contacted local actors in Toscana.31 Since this path is different from the one we theorized, we excluded municipalities in Toscana.

Second, following guidelines for nested analysis and multi-method research (Lieberman, 2005; Seawright & Gerring, 2008), we used the results from our regression analysis to identify a case that exemplified the stable, cross-case association that we found in our statistical analysis. We looked for an “on-the-line” case – one that is close to the regression curve estimated by our main model that minimized residuals (Lieberman, 2005, p. 444; Seawright & Gerring, 2008, p. 89). To do so, we normalized the residuals from our negative binomial regression using Anscombe’s (1948) formula and restricted the universe of potential cases to those in the smallest decile of the residuals’ distribution.

Figure 4 maps the universe of cases for our selection. It plots all municipalities outside of Toscana with a population of less than 25,000 that had active resistance bands in 1943–45. It also situates our selected case, Corvorano, in relation to other potential cases in terms of residuals and the number of signatures as a proportion of the municipal population.

Figure 4. Potential cases by proximity to the regression curve and signature rate.

Note: Dots represent municipalities. The dashed line indicates the mean rate (μ) of signatures over the total municipal population.

Assessing the Statistical Association: Partisan Resistance & Anti-fascist Preferences

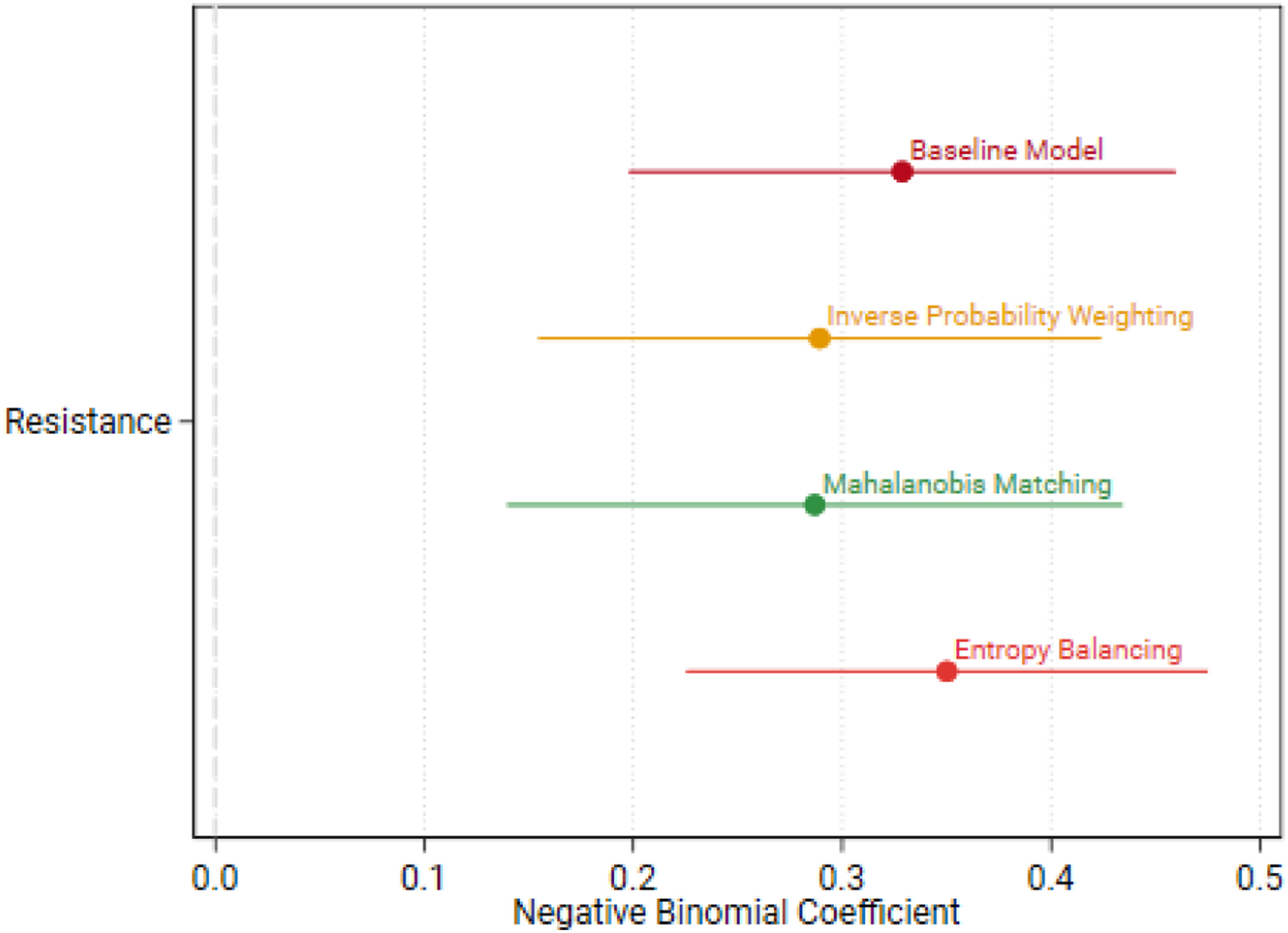

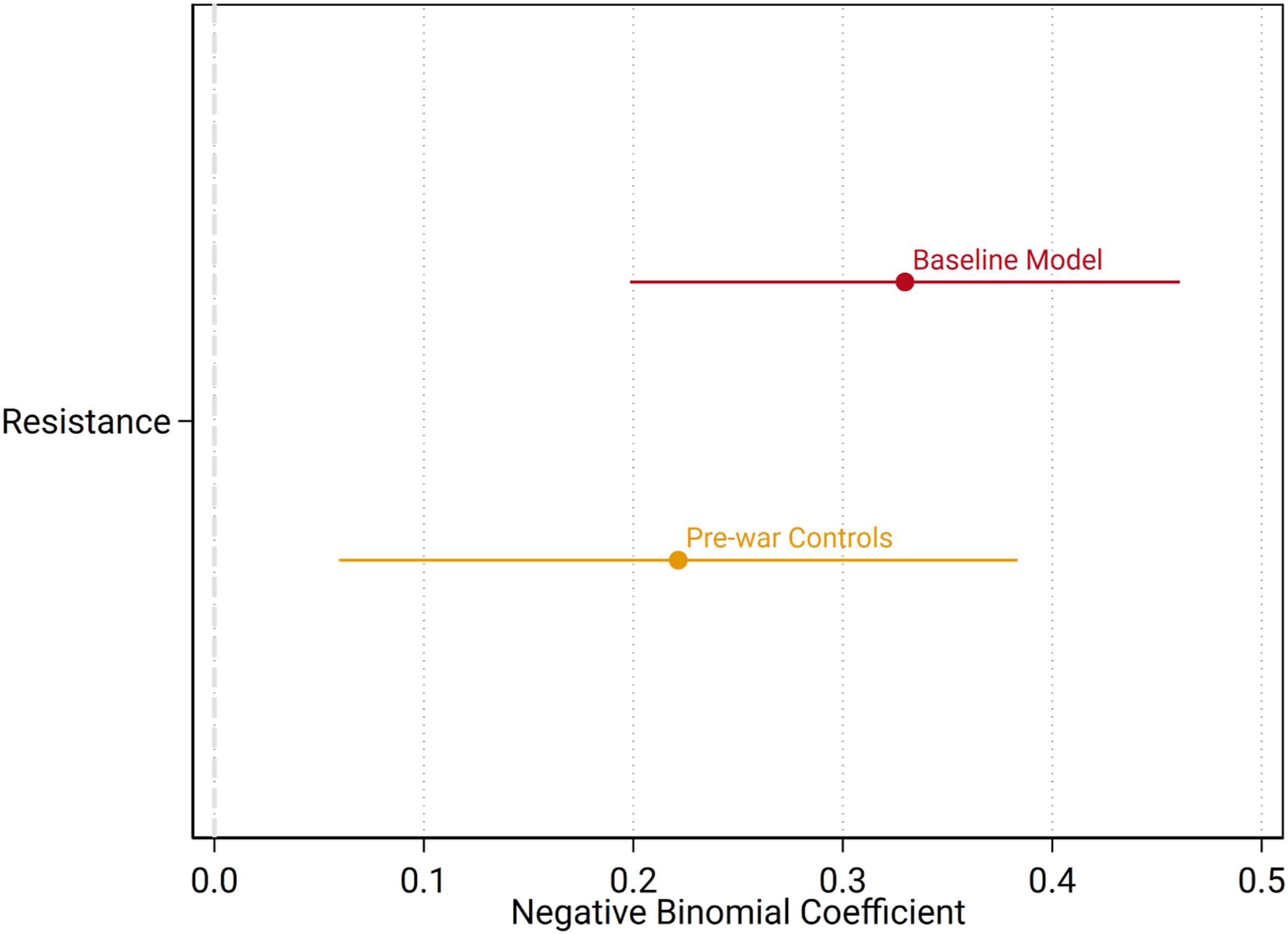

In line with our argument, our statistical analysis consistently shows that municipalities with partisan bands during the civil war more strongly supported the 2020–21 anti-fascist campaign. Figure 5 displays the estimated regression coefficient for our baseline negative binomial model.32 The estimated coefficient of 0.33 indicates a 39% increase in the expected number of signatures in support of the 2020–21 campaign in municipalities that experienced armed resistance between 1943 and 1945.

Figure 5. Presence of partisan bands in 1943–45 and current anti-fascist preferences, adjusting for contemporary controls.

Note: Coefficient estimates (dots) and relative confidence intervals (lines) from negative binomial regressions. Standard errors are clustered at the province level (N = 5330).

This baseline model includes province fixed effects and relevant contemporary controls.33 We account for urban–rural differences by controlling for population size and density in 2021. We control for demographic, social, and economic characteristics that correlate with political orientation, such as the share of the population that is over 65 (2011), employed in the manual and agricultural sectors (2001), university educated (2011), and unemployed (2011). We also include a control for the share of the population with broadband Internet access (2012), as this is a relevant channel of information about the campaign. Finally, we control for the percentage of mountainous terrain in the municipality, which may have facilitated armed mobilization during the civil war (Fearon & Laitin, 2003) and may correlate with current political attitudes.

To investigate the robustness of this association, we performed two additional tests. First, to improve the comparability between municipalities with and without wartime resistance bands, we replicate our analysis on rebalanced samples of matched municipalities on several observable characteristics. We employ three alternative matching techniques – inverse probability weighting, nearest-neighbor matching, and entropy balancing. The results are consistent with those of the baseline model (for more details on this procedure, see Appendix A10). In a second additional test, we demonstrate that municipalities where armed resistance bands were active displayed a different behavior than those where they were not active in a 2020 referendum on an issue area associated with partisan resistance (changing the 1946 Constitution) but not in one held in 2022 on an issue area that is credibly unrelated to (anti)fascism (reforming the judicial system) (see Appendix A6). The fact that these areas do not display systematically different preferences in unrelated policy domains strengthens our confidence that variation in contemporary anti-fascist preferences is linked to past experiences of armed resistance.

Evaluating Competing Explanations

Pre-war Factors & Ideology

The presence of partisan resistance in an area is not random. Since local characteristics that shaped the emergence of resistance in 1943–45 may also be correlated with observable and unobservable factors that could contribute to contemporary anti-fascist preferences, we run a variant of our baseline model controlling for relevant pre-war factors (Figure 6). Although the magnitude of the effect of resistance bands is reduced, the coefficient remains large, positive, and statistically significant. The estimated coefficient of 0.22 implies a 25% increase in the expected number of signatures.34

Figure 6. Presence of partisan bands in 1943–45 and current anti-fascist preferences, adjusting for pre-war controls.

Note: Coefficient estimates (dots) and relative confidence intervals (lines) from negative binomial regressions. Standard errors are clustered at the province level. The pre-war model (N = 3831) includes pre-war controls.

This addresses the concern that the findings of our baseline model could be biased due to the use of controls measured after the civil war (Montgomery et al., 2018; Rosenbaum, 1984). This new model maintains controls for population size and mountainous terrain from the baseline model but substitutes other contemporary controls for a set of pre-war controls that account for socioeconomic characteristics that could be correlated with pre-war political orientations. These include the share of day laborers, sharecroppers, and industrial workers in 1921; number of residents under age 6 in 1911; and the literate population in 1911.35

Local support for communism is one of the main predictors of partisan mobilization during the civil war (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2015b) and the communists were the leading political force organizing armed resistance (Pavone, 1994). Furthermore, the Communist Party created stronger organizations and received more votes in post-war elections in areas where partisan bands were active (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2018; Fontana et al., 2023). Therefore, it is plausible that stronger anti-fascist preferences in municipalities that had partisan bands during the civil war could reflect pre-war ideological preferences. To determine whether this is the case, we control for the share of votes for the Socialist Party in 1919, which at the time included what later became the Communist Party. Our results show that the effect of resistance is independent of pre-war local support for socialism/communism.36

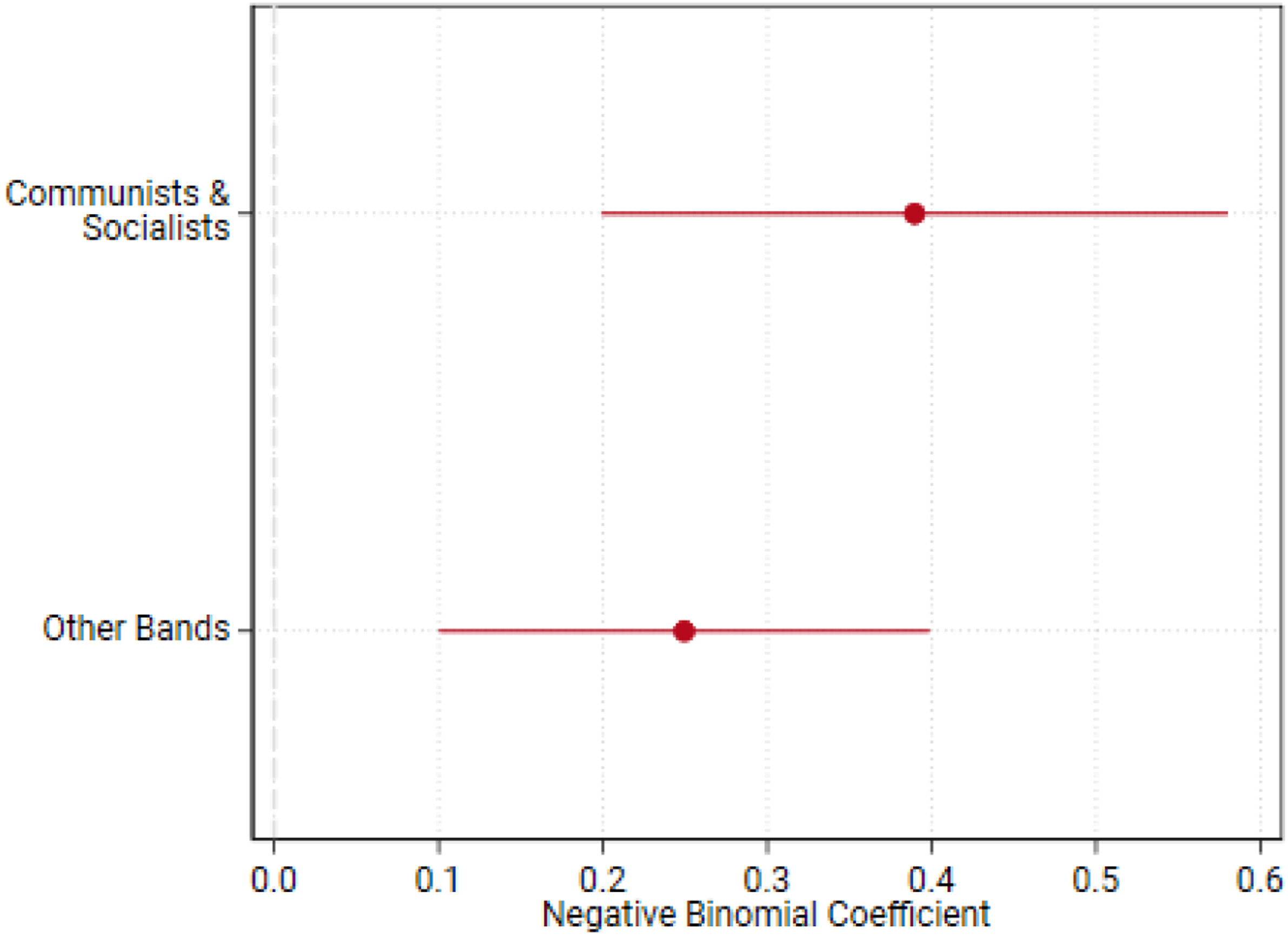

To cast further doubt on this alternative explanation, we re-run our model disaggregating partisan resistance by ideology into two binary variables. The first takes a value of 1 for municipalities that hosted at least one band linked to the communist/socialist bloc and 0 for those with no bands or bands not affiliated with the communist/socialist bloc (e.g., Brigate Fiamme Verdi, Brigate del Popolo, Brigate Giustizia e Libertà; see De Luna, 2021; De Rosa, 1998; Pavone, 1994, pp. 280–303; Vecchio, 2022, Chap 5–8). The second variable takes a value of 1 for municipalities that hosted at least one band not affiliated with the communist/socialist bloc and 0 for those with no bands or bands affiliated with the communist/socialist bloc.37 While we find a stronger effect for bands linked to the communist/socialist bloc using both measures, the effect is not statistically different from that of bands with other ideological orientations (Figure 7). Overall, these results support our core contention that local experiences of resistance can shape contemporary anti-fascist preferences independently of pre-war ideological orientations.

Figure 7. Statistical association between historical local presence of partisan resistance and current anti-fascist preferences, by political leaning of local partisan band.

Note: Coefficient estimates (dots) and relative confidence intervals (lines) from negative binomial regressions. Standard errors are clustered at the province level. Control variables and sample restrictions reflect those applied in the baseline model of Figure 5.

Nazi-Fascist Violence

A consistent finding in the historical legacies of war literature is that exposure to violence has long-lasting effects on political preferences and behaviors. The organizers of the Anti-fascist Law campaign in Stazzema shared this view: they expected greater support for their initiative from the victims of wartime violence.38 While we do not challenge the claim that victimization yields consequential political legacies, we contend that armed mobilization can impact current anti-fascist preferences independently of levels of violence.

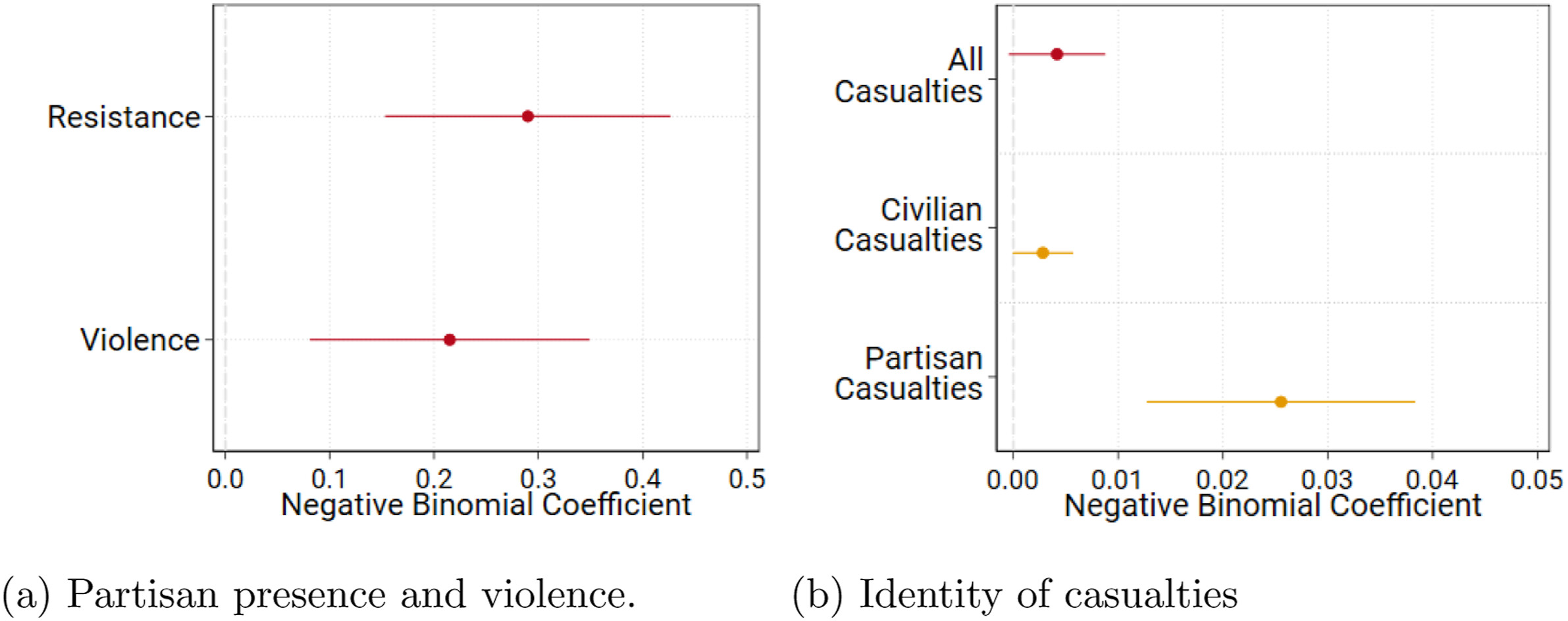

Resistance and violence often overlap. Disentangling them fully requires a different research design and goes beyond the scope of this paper. However, we begin addressing this issue by integrating data on Nazi-Fascist violence into our analyses in two steps. First, we run an additional model that includes a binary measure of municipalities in which Nazi-Fascist forces killed residents in 1943–45. Second, we run separate models estimating the effect of casualties on our dependent variable, using a continuous variable indicating the number of Nazi-Fascist victims disaggregated by civilian versus partisan.

Our findings reaffirm that resistance experiences are an important force shaping current political preferences. When we include a binary measure of the level of Nazi-Fascist violence in each municipality, the coefficient associated with partisan resistance remains stable. Although the difference is not statistically significant, the effect is larger than that of violence (Figure 8(a)). This indicates that partisan resistance is associated with stronger present-day support for the anti-fascist campaign independently of historical levels of violence. Furthermore, while the results of these additional tests show that violence does indeed have long lasting effects, we found that violence against partisans (rather than civilians) drives the effect of violence on support for the campaign (Figure 8(b)), which reinforces the importance of resistance.

Figure 8. Anti-fascist preferences and Nazi-Fascist violence. (a) Partisan presence and violence. (b) Identity of casualties.

Note: Coefficient estimates (dots) and relative confidence intervals (lines) from negative binomial regressions. Standard errors are clustered at the province level. Control variables and sample restrictions reflect those applied in the baseline model.

Exploring the long-term effects of wartime experiences other than violence, such as armed resistance, is important because they likely operate through different channels. For example, unlike violence, memories of resistance do not necessarily revolve around trauma. As such, in addition to leading to the rejection of the identities of the perpetrator (Balcells, 2012), memories of resistance can also forge political preferences and mobilize political action by stressing the political values, ideals, and norms defended by those who resisted.

COVID-19 & Direct Contacts

The Anti-fascist Law campaign was launched in the middle of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the virus did not affect the entire Italian territory equally or simultaneously, the severity and timing of fear of contagion, uncertainty, and movement restrictions varied across regions and municipalities, which could have driven support for the campaign. The province fixed effects in our baseline model likely capture patterns created by contagion and policy restrictions. However, we run tests with region fixed effects and model province-level COVID-19 severity as additional checks. The results are consistent with our baseline estimates (see Appendix A9).

To account for the possibility that the large number of signatures from Toscana could be attributed to personal connections, as campaign organizers in Stazzema suggested, we run variants of our baseline model (1) excluding all municipalities in Toscana and (2) controlling for the distance between Stazzema and other municipalities (to proxy for the strength of personal contacts). The results are also equivalent to our baseline model (see Appendix Table A16).39

Tracing the Process: Keeping the Memory of Resistance Alive

Our statistical analysis shows that support for the Anti-fascist Law in 2020–21 was stronger in Italian municipalities where partisan bands operated during the civil war. This association supports the first part of our argument: wartime experiences other than violence leave legacies that can shape contemporary political outcomes beyond electoral and party politics. In this section, we build on the description from Section 4 of how the winners of the civil war memorialized partisan resistance at the national level to examine, in the case of Corvorano, the other two steps of the intergenerational transmission process theorized above. We offer evidence of how local memory entrepreneurs localize and mobilize collective memories to transmit these legacies across generations and shape current political action.

The Case of Corvorano

Corvorano is a municipality in northern Italy. Most of its territory is rural and sparsely inhabited; almost half of its 10,000 inhabitants live or work in the town center. During the war, several of its residents actively participated in the partisan movement. A few days after the civil war began, residents with various political beliefs formed a local section of the CLN.40 Others soon organized a partisan band that quickly evolved into a battalion of the Garibaldi Brigades – leading actors in the Resistance aligned with the Communist Party.

Three battalion commanders were natives of Corvorano, and at least 15 partisan bases – peasant houses used as shelters, meeting points, and storage for arms and supplies – were established in the municipality.41 Many others supported the partisans: peasants provided shelter and survival goods, children served as dispatch riders, and women organized sabotage operations.42 As a resident explained, “The local band was very much attached to the territory, and the partisans were very close to residents.”43 When the Allies arrived in Corvorano in April 1945, the partisans had already liberated it. In recognition of its contribution to the Liberation and officially institutionalizing collective memory, in the early 1990s, the Italian government awarded the municipality one of the country’s most significant commemorations of gallantry, the Medaglia di Bronzo al Valor Militare.

Corvorano’s immediate post-war politics showcased its partisan and anti-fascist identity. The first two mayors, one nominated by the CLN and the other elected, were communists with links to the resistance movement. In the June 1946 referendum, over 85% of Corvorano’s residents voted in favor of the republic and against the monarchy, the institution that had legitimized the rise of fascism (the national percentage was 54%).44 The memory of partisan resistance and this anti-fascist identity remains central to Corvorano’s politics. In April 2021, support for the anti-fascist campaign was roughly twice the national average.

Public memorialization efforts did not start immediately after the war. In addition to the national political dynamics cited above (see also Cooke, 2013), residents highlighted several different reasons why those who had taken part in the local resistance movement sought to put the events behind them or at least to not making them too salient. These include trauma from the experience of war and the desire not to remember the atrocities witnessed or carried out during that period, the need to protect those responsible from possible retaliation and post-war political violence, and the desire to recreate a sense of unity within the community by forgetting the wartime divisions and wrongdoings.45

Yet, the drive to remember began in earnest in the 1970s. Observational, archival, and testimonial data illustrate residents’ persistent efforts to preserve the collective memory of the Resistance and anchor it to the local experience over the past five decades. These efforts have been crucial to transmitting this legacy across multiple generations (see the timeline in Table 1). Consistent with our expectations, we found strong evidence of an active network of local memory entrepreneurs (with sympathies across the political spectrum) who have championed localized physical and experiential memorialization initiatives involving residents from different generations from the 1970s until now and mobilized residents to support the Anti-fascist Law in 2020–2021.

| 1945–65 | Period of “silence” |

| 1965 | Map of Nazi and partisan bases |

| 1971 | 1st professor invited to talk about resistance in the region |

| 1976 | Community renovation of memorial stones |

| 1976 | Diplomas awarded to families of 37 fallen partisans |

| 1976–77 | Municipal commission renames 37 streets after fallen partisans |

| 1977–81 | Grassroots radio station explores local partisan history |

| 1994–95 | Primary-middle school research for Il Valore |

| 1995 | City Hall square monument for fallen partisans |

| 1996 | Publication of Il Valore |

| 2004 | Creation of memoriae |

| 2005 | Documentary exhibition on local partisan band |

| 2007 | Photo collection “local places of resistance” |

| 2009–10 | Screening of resistance film L’uomo che verra |

| 2010 | Establishment of memory coordination table |

| 2015 | Book and DVD on partisan street renaming |

| 2017 | Documentary on the history of allied forces in the territory |

| 2018 | Creation of memory trekking and biking trails |

| 2020–21 | Signature collection for anti-fascist law |

| 2022 | Opening of the garden of memory |

Anchoring Collective Narratives Locally

We arrived in Corvorano in April 2022, just before Liberation Day. Residents had recently opened a Memory Garden commemorating local Resistance members and were preparing a community lunch to celebrate the 77th anniversary of the Liberation and a tour of local partisans’ tombstones. Given the occasion, it was no surprise that multiple efforts to memorialize the Resistance were underway. Yet it quickly became clear that these efforts went above and beyond Liberation Day. For some residents, memorialization is an almost permanent endeavor. As a former mayor of Corvorano explained, “if [memory work] is not constantly fed, it gets lost.”46 A former cultural advisor asserted that paying attention to “the local memories that contribute to building the story of our territory” is crucial for effective memory work47 This work entails physical as well as experiential memorialization, which we discuss in turn.

Physical Memorialization

Corvorano’s public spaces are repositories and amplifiers of memory. The road we took to the City Hall – Corvorano’s main artery – is named the Street of the Fallen of Grand Avenue (Via Caduti di Via Grande); several other urban and rural streets also recall the Resistance and Liberation.48 A section of the central cemetery is devoted to partisans, and the main square features a large monument depicting a mother holding her son fallen in the country’s fight for liberation. A plaque by the entrance to the City Hall reads: “Imperishable glory to the heroes fallen for the freedom of the fatherland” – a reference to casualties among the partisans rather than soldiers in the regular army.

While many Italian towns have streets and squares named after well-known anti-fascists or have names related to the partisan resistance and the country’s liberation, like Via Giacomo Matteotti and Piazza della Libertà, Corvorano is different in this regard. In the mid-1970s, on the 30th anniversary of the Liberation, a multi-party commission was created to change street names to commemorate the partisans. While everyone favored the initiative, the nature and extent of it – what memory scholars call the “scaling of memory” (Alderman, 2003) – was contested. The Christian Democratic minority pressed to keep it generic, as in many other places in the country, while the communists and socialists proposed to dedicate a street to every fallen partisan from Corvorano. The latter proposal eventually prevailed, and 37 street names were changed. Street names now combine generic references to the resistance movement with localized recollections of the municipality’s contribution to it, such as the names of local partisans or the local brigade.

Official documents from the time assert that the actors behind this initiative were aware of the significance of naming streets to keep the memory of the Resistance alive: “Streets are part of the identity of a municipality because they host past and present events that contribute to creating the community’s collective memory. Streets are, consequently, places of memory par excellence.”49 Testimonial data suggests they were also mindful of the importance of anchoring the project in the municipality’s specific experience. Without being prompted, Francesco, the head of Memoriae – one of the most active cultural associations doing memory work in Corvorano – explained that “using the names of local heroes …makes it all more real, closer to the people, easier to relate to …New generations might not know who these people are, but they would ask, and we can tell them the story.”50 While assessing systematically the impact of physical memorialization is beyond the scope of this paper, archival data shows that residents of different generations explicitly acknowledge its importance. Referring to monuments, plaques, and tombstones, Corvorano’s school students stressed in the mid-1990s that “…as long as time will not consume the stones themselves, these names and dates [of the partisan resistance] will not be canceled from our memories.”51

Experiential Memorialization

Experiential memorialization allows people to learn about and identify with the past by actively participating in memory making. Unlike its physical counterpart, it offers the opportunity to target and actively involve people from multiple generations and different walks of life. Memory entrepreneurs in Corvorano worry that the more temporally distant the experience of resistance, the less the public will identify with it. Experiential memorialization initiatives have allowed them to involve a diverse set of residents, targeting younger generations in particular.

The local school has perhaps been the central space for experiential memorialization in Corvorano. University professors have been regularly invited since the late 1970s to give talks about the Resistance to students, and several movies about the Resistance have been screened for them, including The Man Who Will Come (L’uomo che verra) in 2009 and 2010.52 Gloria, who has run Corvorano’s local library for decades, described these experiences as “key moments of mutual recognition” between kids and the older generation who fought for Liberation and considers them essential to “make sure that the word ‘memory’ doesn’t only evoke a tombstone.”53

These events have encouraged teachers and students to dig deeper into the local history of resistance. On the 50th anniversary of the Liberation in 1994, for example, a group of teachers and students consulted secondary sources and interviewed local survivors to map the most significant local events and places associated with Corvorano’s partisan resistance and Nazi-Fascist violence. These activities have been crucial for localizing and transmitting collective memories. Not only did the City Hall officially sanction these memory-making efforts by distributing print-outs of the findings to all residents, but students noted that the project taught them “about the facts and the people that enabled us to conquer the freedom and the democratic way of living on which we all live now.”54

Beyond actively involving multiple generations, experiential memorialization initiatives in Corvorano have sought to reach different segments of the population. Without probing, the current cultural advisor to the mayor’s office stressed that “memory work makes sense if we amplify and diversify the public […] If we use different instruments, like arts, and learn how to speak the language of different people, we can get more and more people onboard.”55 Consistent with these claims, several memory initiatives have been linked to various cultural and sports activities. For example, memory entrepreneurs have partnered with the local chapter of the Italian Alpine Club (Club Alpino Italiano, CAI) to rehabilitate old partisan paths and organize hikes for residents and visitors. Similarly, they have collaborated with a local cycling club to organize rides through the territory using partisan tombstones as itinerary markers.

Many similar initiatives have been organized, some of which were designed to be permanent; some were ongoing during our fieldwork.56 As with physical memorialization, assessing the impact of these initiatives is beyond the scope of this paper. Yet, testimonies from those involved in experiential memorialization suggest that these experiences have helped socialize younger generations and less politicized residents into the narrative of the Resistance and the values it upholds.

Mobilizing Collective Memories

The percentage of signatures collected in support of the anti-fascist campaign in Corvorano was more than double the national average. This is especially noteworthy given three key obstacles the signature collection faced in Corvorano. First, signatures were only collected in the main urban center in what is a sparsely populated municipality with poor connections to rural areas. Second, roughly 20% of Corvorano’s residents recently moved there and use it as a commuter town; they are less involved in the town’s life, identify less with it, and seldom participate in initiatives or support this type of campaign.57 Finally, COVID-19 mobility restrictions were particularly stringent in the municipality.

This strong support for the anti-fascist campaign can be at least partly attributed to the mobilizing efforts of local memory entrepreneurs. While City Hall endorsed the campaign,58 mobilization was undertaken from the bottom up. Memoriae and ANPI set up a tent by the main supermarket entrance to inform residents about the campaign and collect signatures. This strategy likely helped them obtain more signatures for two reasons. First, information about the campaign was not widespread (especially offline). Therefore, raising awareness of its existence was important. Moreover, having Memoriae and ANPI disseminate information highlighted the association between what was at stake in the present and the Resistance past, which has been found to strengthen the impact of collective memories on present behavior elsewhere (Fouka & Voth, 2023). Second, accessing signature forms was not easy, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. In many other municipalities, people could only sign at the City Hall. Thus having access to the forms at the supermarket likely made a difference, especially since grocery shopping was one of the few activities not fully suspended during the lockdowns.

However, memory entrepreneurs stress that they did not convince people to sign: “people signed because they are antifascist, not because someone told them to do so.”59 Residents supported the campaign because they felt a strong ideological connection to it.60 A former mayor of Corvorano insisted that these signatures were only the “tip of the iceberg.” To him, support for this campaign reflects the values sown by the partisans that many in the territory still defend.61 While these actors might have reasons to aggrandize their role in the campaign’s outcome, the evidence we collected strongly suggests that underlying those signatures are decades of hard work to preserve the memory of the Resistance, as well as a concrete effort to activate these memories when they come under threat. This successful mobilization of support for the anti-fascist campaign is a testament to the fact that, as Corvorano’s cultural advisor explained, “memory is not only to remember what happened in the territory but also not to forget what we have to fight against in the present.”62

Memory Entrepreneurs

The process tracing literature often describes mechanisms as entities (or actors) engaging in activities (Beach & Pedersen, 2019). Memory entrepreneurs are the actors behind memorialization, localization, and mobilization, and Corvorano has an extraordinarily active and well-organized network of such actors that is comprised of cultural and civic associations with various political leanings. ANPI, as expected, is a critical node, working to preserve and promote the memory of resistance since the war’s aftermath.63 While the ANPI is represented throughout the country, Corvorano’s local chapter, with about 80 active members, is particularly robust. Its president from the early 2000s explained that while presiding over the ANPI elsewhere typically involves organizing two or three activities per year, in Corvorano he organized activities almost every month.64

Memoriae, created in 2004 and headquartered in the town’s ARCI, has been involved in almost every memory-related activity organized in the municipality since its creation. These include projects such as the Memory Garden and producing a wealth of documentary material, including leaflets, books, and DVDs. While ANPI is largely a political association with solid links to the Communist Party, Memoriae is a cultural center for social aggregation. Most of its founding members and directors are decisively left wing, yet they try to remain independent from party organizations. They believe this gives them more flexibility in their work and allows them to involve residents from different walks of life.65 Like several memory entrepreneurs in Corvorano, Memoriae stresses that what unites them is not a party or leader, but an unwavering anti-fascist sentiment.

While some of these local memory entrepreneurs are relatively recent, an older resident reminded us that memory work “has deeper roots” in the work of the ANPI, the Communist Party and other local experiences, and that the current associations are “building on work that was already there.”66 Yet, while Memoriae represents the institutionalization of many local initiatives that date back to the 1970s, it did not emerge from the ranks of the ANPI or the Communist Party. Many interviewees, including some of its founding members, identified a grassroots local radio station as a foundational antecedent of Memoriae and other local associations engaged in memory work. The station operated from 1977 to 1981 from a house that served as a partisan base during the war. While those involved acknowledge that they were not fully aware of the importance of preserving collective memory at that time, and the radio’s attention to it was mostly limited to April 25 (Liberation Day), some programs investigated Corvorano’s partisan history.67 These interviewees described the radio as a “civic commitment” and noted that “in a partisan territory …[this commitment] is naturally related to that past.”68

These memory entrepreneurs led so many initiatives that in 2016 Corvorano’s municipal administration established a Memory Table to coordinate and align their projects with its own. Many of these actors have worked closely with multiple municipal administrations, regardless of which party is in power, and several individual memory entrepreneurs have moved between local government and civic associations.69 Yet, this does not mean their work is “institutionalized,” let alone co-opted by the local government. On the contrary, their strong standing within the community has allowed them to influence the administration’s memory agenda. At the time the fieldwork was conducted, there were some political differences and tensions between the local administration and key memory entrepreneurs. Still, the mayor recognized that “these associations are vital for the administration; they are Corvorano’s active citizenship and a channel of contact with ordinary citizens.”70

All in all, Corvorano is a prime example of community-based transmission. Unlike other contexts in which transmission has been primarily channeled via family ties (Acharya et al., 2018; Lupu & Peisakhin, 2017) or where the community has been important for transmission because it amplifies the family’s influence (Charnysh & Peisakhin, 2022), Corvorano offers evidence that community-based transmission can be independent of family ties. To our surprise, none of the critical memory entrepreneurs in Corvorano had family links with partisans. They attributed their involvement in memory work to what they referred to as a “civic commitment.” However, they recognize that having partisan families in the area provides fertile ground for memorialization, and they have involved these families in memory-making activities.71 For example, students in the 1990s interviewed partisans and their relatives to reconstruct the local history of resistance, and the CAI worked with them to rehabilitate old partisan trails. Moreover, memory entrepreneurs stress that conversations with partisans were crucial for translating the “national narrative” of Resistance and Liberation into a localized collective memory of what happened in the territory.72

Conclusion

Do wartime experiences other than violence leave long-lasting political legacies? Can collective memories of armed resistance shape people’s contemporary political attitudes? Can these memories be activated to incite current political action beyond the ballot box? We explored these questions in Italy, investigating whether (and how) local experiences of partisan resistance against Nazi-Fascist forces during the country’s civil war help explain support for a recent anti-fascist grassroots legislative campaign.

We argue that the political legacies of wartime resistance can survive over time, be passed down from generation to generation, and affect contemporary political outcomes via a process of community-based intergenerational transmission of collective memories. This process consists of three crucial activities advanced by both national and local memory entrepreneurs: (1) forming a national-level collective narrative of the resistance experience that commemorates the political identities of the resisters (memorialization), (2) anchoring this narrative in the concrete experiences of local communities to increase resonance (localization), and (3) activating these collective memories and translating them into political action when the values of the Resistance are under threat (mobilization). Our statistical analyses consistently demonstrate that residents of areas where partisan bands operated more strongly supported a contemporary anti-fascist campaign. Our qualitative analyses offered within-case evidence of the workings of the transmission process in one purposively selected case.

This study makes three key contributions to the growing body of work that examines how wartime experiences affect peacetime politics over the long term. First, we join a small group of recent studies (Balcells & Villamil, 2023; Barceló, 2021; Lazarev, 2019; Osorio et al., 2021) that shift away from the dominant focus on wartime effects on electoral and party politics. By concentrating on mobilization for a grassroots legislative campaign, we show that wartime experiences can have political effects beyond the ballot box. This is particularly important for Italy, where recent studies have shown that while the civil war shaped post-war electoral politics and party organization, these legacies have progressively faded away since the disappearance of the Communist Party in the late 1980s (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2018; Fontana et al., 2023). Our study demonstrates that the war’s legacies have outlived the existence of the Communist Party, and that they do not fully depend on ideological commitments to communism and socialism. In Appendix A7, we examine electoral outcomes and provide suggestive evidence that the presence of resistance bands may also have tangible consequences for contemporary electoral politics. Future research should further theorize this relationship and systematically test it.

In a second contribution, we expand the study of the long-term effects of war by examining the legacies of wartime experiences other than violence. Our main statistical analysis displays a robust association between local resistance and contemporary anti-fascist preferences, while additional tests suggest that this effect is independent of fascist violence. Moreover, our qualitative analysis reveals that local experiences of resistance can be a powerful source for the formation and transmission of collective memories. This suggests that wartime legacies do not need to stem from violent victimization or rest on trauma. Moreover, wartime experiences like armed resistance not only stimulate the rejection of the perpetrators’ political identities; they also actively promote the identities of the resisters. Further research should more closely explore how the processes linking past wartime experiences to contemporary political outcomes depend on the type of wartime dynamic.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we advance the study of mechanisms of transmission. Scholars of political legacies have identified multiple variables and conditions that sustain transmission or enable persistence, ranging from family socialization to clandestine networks. We took a different approach and theorized a process and offered detailed qualitative evidence of how it operates within a single case. Contributing to a long-standing debate on the role of family and community in persistence (Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman, 1981; Charnysh & Peisakhin, 2022), our study suggests that communities can transmit legacies and activate them even in the absence of family ties or widespread parental socialization. Recent research has shown that collective memories are more likely to influence present-day behavior if they are institutionalized by the state (Fouka & Voth, 2023). Appendix A8 provides additional quantitative evidence supporting the claim that the institutionalization of memory matters. However, our qualitative data establishes that local communities play a role in memory institutionalization and, even when state sanctioned, memorialization can be more powerful if anchored to concrete local experiences.

The process we theorized and traced is sufficient to explain the link between eventful past experiences and present political attitudes and behavior in the case we examined and could travel to other causally homogeneous cases. However, other pathways might well operate in other cases. Future research should explore other “typical” cases to probe the generalizability of this process and explore alternative pathways. We hope our effort to carefully theorize and trace processes linking past events with contemporary political attitudes and behaviors illustrates the benefits of integrating different approaches to the study of long-term legacies.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to everyone who made our fieldwork possible, particularly those who participated in our study. We also thank Anagrafe Nazionale Antifascista, Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia, Associazione Ricreativa Culturale Italiana Milano, Istituto Nazionale per la Storia del Movimento di Liberazione in Italia, Francesco Colombo, Cristina Franceschi, Gloria Gennaro, Giacomo Lemoli, Andrea Ruggeri, and Stefano Costalli for helping us collect the quantitative data. For comments on previous versions, we thank Danilo Bolano, Stefano Costalli, Catherine De Vries, Elias Dinas, Florian Foos, Giovanna Marcolongo, Zach Mampilly, Zach Parolin, Andrea Ruggeri, and participants in Leiden’s “Conflict Cluster Retreat” and “Political Science Seminar,” the UNU-WIDER Workshop “Institutional Legacies of Violent Conflict,” Bocconi’s “Politics & Institutions Clinic,” Wageningen’s Workshop “Spaces of Governance Workshop,” the BIGSSS Lecture Series, and the European University Institute’s “Political Behavior Colloquium.” Nicola Bariletto, Giulia di Donato, Sara Luxmoore, and Giuseppe Spatafora provided superb research assistance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests