DOI: https://doi.org/10.59350/6h126-15k51

This is a guest post by Jessica Nina Lester (Indiana University), Noah Goodman (Education Development Center's Center for Children & Technology), & Michelle O’Reilly (University of Leicester)

In 2018, we began talking to one another about how qualitative researchers might expand the analytic approaches that they use when working with qualitative data, particularly those researchers working in applied contexts. We approached our questions around qualitative data analysis from different contexts. Noah worked as an applied researcher, while both Jessica and Michelle were qualitative methods faculty in institutions of higher education. Yet, we consistently came to the same conclusions; that is, qualitative researchers rarely use analytic methods outside the mainstay approaches of their disciplines. And, for many disciplines, the primary qualitative analytic method used is thematic analysis. While we view thematic analysis as generative and central to our own work, we also recognize that there is a vast – often untapped – landscape of qualitative analytic methods available.

It was our collective commitment to considering what else might be analytically possible, particularly for applied researchers, that led us to team up to develop a special journal issue for The Qualitative Report. This special issue brought together a wide range of scholars who use varying qualitative analytic approaches in their work. The goal was to offer a “useable methods map” to support researchers as they learned to work with qualitative analytic approaches—some of which might be new to them.

To produce these “methods maps”, we thought it would be useful to invite the issue’s contributors to analyze a shared dataset. Specifically, we secured a dataset stored in the Qualitative Data Repository (QDR) from a study exploring “postnatal care referral behavior by traditional birth attendants in Nigeria”. In July 2006, Chukwuma and colleagues collected this data as part of a larger mixed-methods study examining stakeholders’ perspectives on postnatal care referral behaviors of Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) in South Eastern Nigeria. The original researchers conducted three focus groups—one with eight health care workers (HCWs), one with 10 TBAs, and one with 10 clients of TBAs. All of the focus groups, ranging from 62 to 87 minutes in length, were audio-recorded and conducted in either English or Igbo. The dataset consisted of the focus group transcripts, the scripts researchers used to run the focus groups, consent forms, and contextual information about the data collection and research site.

We envisioned analyzing a shared dataset using a range of methods would allow for unique and diverse analytic contributions and insights to become more visible. The contributing authors introduced and illustrated a broad array of analytic approaches, including thematic analysis perspectives, the “sort and sift, think and shift” approach, framework analysis, discursive psychology, and a new materialist perspective. And, we saw in this issue, even within thematic analysis there were diverse approaches used. We also included in the special issue an article authored by scholars from QDR about the responsible reuse of qualitative data.

Benefits of Engaging with Shared Data

Through the course of producing this special issue, we reflected on the benefits of data sharing and secondary data analysis (i.e., using the data produced by another scholar for one’s own intellectual purposes). We view the benefits as both pedagogical and substantive.

From a pedagogical perspective, we see benefits for both primary and secondary researchers. Working with well-documented secondary data can provide a valuable window into another researcher’s process—from how they went about their consenting human participants to the ways they used protocols to build conversations in focus groups or interviews. We rarely get this type of access, and when we do it’s often from others close to us who may already share our general approach, such as mentors, advisors, or colleagues.

Throughout the issue, and during the subsequent panel we convened at the Qualitative Report’s 13th Annual Conference, we heard contributing authors envision alternative approaches for the postnatal care referral project. They wondered whether participants might have expressed themselves differently if the focus groups were conducted in a community center rather than the local hospital, or noted ways they might have strengthened the alignment between the research questions and the data collection methods. Analyzing others’ data seems to encourage these types of reflections that can be generative in themselves and allow researchers to reflect on their own work.

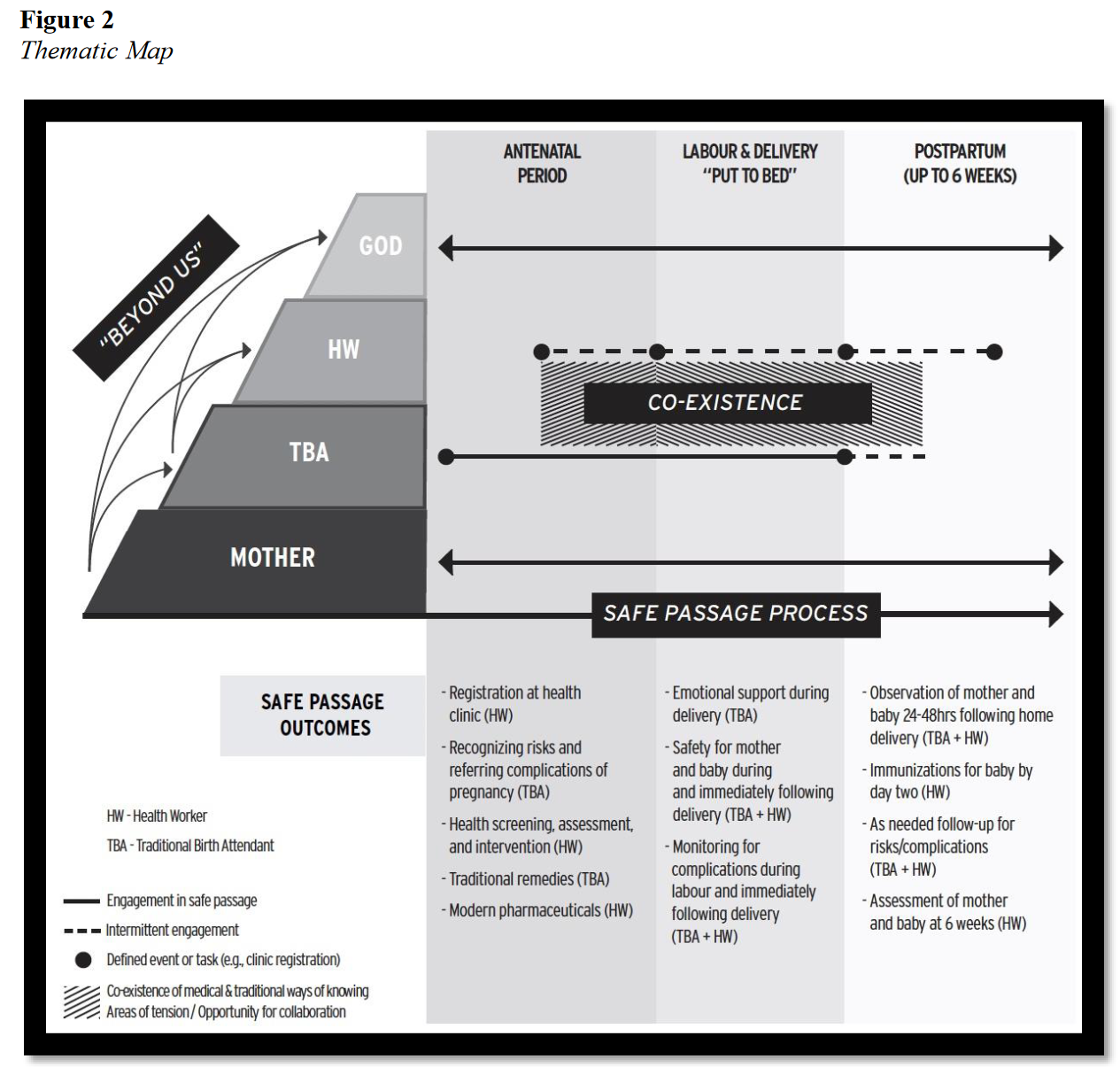

From a substantive perspective, while most of the articles in the special issue identified certain themes, such as the power dynamics between the TBAs and HCWs, they also highlighted different aspects of the data underlying the study. For instance, the article on framework analysis used data intensity mapping to note the extent to which each participant group discussed different topics and to highlight silences in the data that might be meaningful for relationships between TBAs and HCWs. By contrast, the article using reflexive thematic analysis developed a thematic map to identify moments in the birthing process where there were opportunities for cooperation between TBAs and HCWs. These differences in the types of information authors were attuned to stemmed both from the authors’ analytic lenses and their professional backgrounds. The authors’ primary goal was to illustrate a) a process for using their chosen analytic approach, and b) the types of findings their approach produces, rather than to develop substantive findings about the referral practices of TBAs. Nonetheless, the range of substantive themes and conclusions featured in these papers highlighted the value of opening data up to secondary interpretation. Analyzing the same data from different perspectives produced insights and understandings that would not otherwise have been attained.

Challenges of Working with Shared Data

We asked contributing authors to point to some of the challenges they faced when working with shared data. They noted several challenges, highlighting that secondary data analysis is not a simple endeavor.

Many authors pointed to how the application of a particular analytic approach is largely dependent on the volume and quality of the data available – which in the case of the shared dataset we used was viewed by many of the authors as being limited. The amount and nature of the data available to a secondary analyst is at times challenging depending upon the analytic approach used by that analyst. Likewise, the quality of the data results – at least in part – from the insider knowledge the original researcher develops due to their relationships with participants. For example, fieldnotes, memos, and memories of how things were said by participants often shape researchers’ final set of findings. When an analyst is entirely removed from the data collection process, the benefit of relationship building is absent. For some approaches, this may be argued as a strength, but for others it could be a deficit.

Another core challenge that some of the authors highlighted was how the underlying assumptions of the method they sought to use to analyze the data were not necessarily aligned with the type of data available in the shared dataset. For example, in the article focused on discourse analysis, the authors noted that not having audio or video files available made it difficult (if not impossible) to examine the details of the interaction. Even still, the authors noted that while there were certainly gaps in what they could do in their analysis, they were still able to identify unique and meaningful findings.

Several of the contributing authors also noted that there was contextual information that would have helped them better analyze the shared data set—such as more demographic information about the focus group participants. Researchers who begin a project with data sharing in mind might be moved to collect and retain different kinds of information, or strengthen their approach to data management from the start, thus ensuring that their data is securely stored and documented in a manner that enhances their own ability to draw meaningful conclusions.

The Futures of Shared Data for Qualitative Researchers

We left this project with several conclusions. First, carrying out the study reinforced our belief in the value of open science and the idea that qualitative researchers should seek – when appropriate and possible – to make their data available to others. Every time a researcher collects data it represents an investment of time and resources, and especially when those resources come from publically available funding, such as federal grants, we should seek to maximize the benefit. QDR provides valuable resources that researchers can use to make this a reality. These include suggestions for appropriate language that can be incorporated into consent forms, and for how best to work with ethics boards to collect data that can be shared with others while also protecting research participants. That said, there are lots of ethical implications with sharing data and therefore it is important for qualitative research communities to continue discussions both about the value of data sharing and under what circumstances it is appropriate. Of particular importance is to consider how best to seek consent from participants to share more broadly the information they offer in a research interaction.

We think this latter consideration -- that is, participant consent related to shared data -- is of particular interest. Some research participants may not have a clear understanding of the research process, what a dataset looks like, what it might mean to de-identify data, and how data might be repurposed by other researchers. It is hard to imagine, for example, that the Nigerian mothers or TBAs who participated in the focus groups in the study that formed the basis for our project—or the researchers who collected the data for that matter—could have imagined that their experiences would then be re-analyzed by researchers in North America and Europe as part of a methodological experiment. It will be important for qualitative researchers to continue to improve how they inform participants about what data sharing means and the measures that will be taken to protect their privacy. Finally, our experience co-editing this special issue highlighted the importance of including rich contextual information about the participants, the context, and the goals of the research, as ethically possible, when sharing a dataset.

Even with these caveats, we feel these gaps and areas of ongoing questioning point to the futures of shared data in qualitative research. Secondary analysis of qualitative data is an area of practice that deserves far more attention in the coming years, particularly as the landscape of research continues to evolve and shift in response to the historical present.